The Global Corruption Barometer (GCB), published by Transparency International (TI), an international organisation specialising in corruption and anticorruption policy, is something of a “voice of the people” – a widespread survey conducted on nationwide samples.

Together with the better-known Corruption Perceptions Index, which is based on expert assessments, it offers a complete picture of how both specialists and “ordinary” citizens perceive corruption in various countries. TI’s extensive report on the latest research, which took place between October and December 2020, compares the views of citizens in all EU countries, 40,000 of whom participated.

A bleak outlook in Europe

TI’s research shows that 62% of respondents in 27 European countries think that corruption is a big problem, while a third said that it had increased in the year preceding the survey. The most pessimistic in this respect are the Cypriots (65%), Slovenians (51%) and Bulgarians (48%), while the Finns (16%), Estonians (18%) and Slovaks (19%) are the least concerned.

Half of all respondents believe that their countries’ governments are not coping with corruption. More than half (53%) also claim that their governments are guided by the interests of big business and narrow groups.

And the COVID-19 pandemic has not improved the verdict on states’ anticorruption activities: less than half (44%) of Europeans agreed with the claim that their governments’ response to the pandemic has maintained standards of transparency.

European Union citizens also believe that public officials tend to get away with corruption – just 21% say that those guilty of corruption are adequately punished. EU institutions are trusted by 56% of respondents, while 64% trust local government.

The same percentage, meanwhile, think that citizens can make a difference in the fight against corruption. Unfortunately, the worst result in this respect is recorded by Poland, which is the only country where a majority (57%) say that ordinary people cannot make a difference (just 23% Poles say they can).

Alarm bells in Poland

Poland does not fare particularly well overall in the Barometer– another alarm bell after the Corruption Perceptions Index published at the start of this year. Almost three quarters of Poles (72%) say that corruption is a big problem in the country. Some 37% think that the level of corruption increased in the 12 months before the study, 20% say it decreased, and 34% that it did not change.

The respondents counted the government administration (34%), the office of the prime minister (32%) and the parliament (31%) as the most corrupt public institutions, while 25% said the president’s office was corrupt. Courts (20%), the private sector (also 20%) and local authorities (21%) come out relatively well. The least corrupt entities according to Poles are the police (10%) and NGOs (12%).

According to two thirds of respondents from Poland, the government is not dealing well with corruption. A similar proportion (61%) agreed with the statement that “the government is run by a few big interests looking out for themselves”. Meanwhile, just 16% of Poles think that appropriate actions are taken towards public officials.

A relatively large number of Polish respondents think that the authorities instrumentalise corruption for their own particular objectives – 21% agreed with the statement that “It is acceptable for the government to engage in corruption as long as it delivers good results.” Just 25% thought that the measures taken by central government to combat the pandemic are maintaining transparency standards.

The poor corruption ratings of national government chime with very low trust. Some 78% of respondents declare a lack of trust in the government, 46% of them saying they have no trust. A large majority of Poles (78%) do not trust the government, and 60% do not trust courts. Exactly half say that they trust the European Union, and 44% trust local government.

The police recorded a good result for trust – with 52% of people in Poland declaring a positive view. (In Poland, the study took place between 13 and October and 15 November 2020, and the data therefore do not reflect the effect of the mass protests taking place at the time, which national surveys show to have seriously undermined trust in the police).

Diminishing bribery

The Polish responses also show that in the 12 months before the study 10% had paid a bribe hoping to get access to one of the public services mentioned: education, health care, social care, the police, courts, and public administration. Incidentally, the same percentage of respondents declared that in the five years before the research they had provided sexual favours as a bribe.

Bribes were most often given in health care (10%) and contacts with the police (6%). Compared to the 1990s and the early part of this century, declarations of giving bribes are much rarer. In similar research conducted in Poland in this period by the Centre for Public Opinion Research (CBOS), as many as 20% said they had given a bribe.

In a joint study by the Batory Foundation and CBOS in 2001, as many as 36% of people declared that they had had to give some kind of material benefit (money or a gift) to a doctor or other medical worker in the previous decade in exchange for access to a medical procedure.

As far bribery is concerned, then, the situation in Poland is far removed from how it was 20 or 30 years ago, as well as in Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary, where 20%, 19% and 17% of respondents respectively had been forced to give a bribe in the last year.

Yet the Polish result, owing to underestimation, is also a concern. In Scandinavian countries, 1% of respondents declared that they had given a bribe. Interestingly, even Spain and Italy, regarded as countries with systemic corruption, had only 2% and 3% of people who admitted to having given a bribe in the previous year.

How can corruption be reduced?

What practical lessons can be learned on anticorruption policy from the Barometer? Transparency International’s report suggests several directions. Above all, governments should do more to increase citizens’ trust in public institutions – for example offering them a transparent, inclusive way of making public decisions and facilitating social control of government (by increasing access to public information and protecting media freedom).

They should be open to dialogue with citizens, businesses and interest groups. At the same time, states should ensure appropriate regulation of lobbying and laws enabling effective management of conflict of interests to prevent it from turning into corruption. One aspect of citizens’ trust in the state – creating an environment conducive to the fight with corruption – is ensuring that whistleblowers informing about corruption and fraud in their workplace are protected.

High indicators of using patronage when accessing public services means that we should consider increasing transparency and social control over this huge area of responsibility of every state. The situation, as TI suggests, could be improved by wider use of digital tools.

These could significantly increase transparency and access to all kinds of public services, as well as to public procurement procedures, which should have been fully digitised long ago. The state should also proactively make more public data available in open data formats.

All the recommendations made in the Transparency International report can in fact be addressed to Poland. Particularly, we can mention improvement of access to public information and ensuring media freedom. In Poland, however, the government appears to be working in exactly the opposite direction. The media are being bought by state companies like in Russia.

Hundreds of parliamentary questions to the government have gone unanswered, although the law has been broken. Meanwhile, citizens could soon lose the right to public information almost completely. After all, in a motion to the Constitutional Tribunal earlier this year, the first president of the Supreme Court questioned many key provisions on access to public information.

On the other hand, since 2015 the government has not reformed the laws on disclosure of assets of politicians and officials and their families. Despite promises, the system for completion and publication of financial interests has also not been digitised. Civic and social dialogue are disintegrating – the government is avoiding consultations and breaking all rules of correct legislation, limiting citizens’ opportunities for influencing statutory law.

Polish lobbying laws are as full of holes as they were when they were passed in 2005. For more than two years, the government has done practically nothing to implement the EU’s Whistleblower Protection Directive – the time limit is the end of this year. Many specific anticorruption solutions are lacking, including those foreseen by the UN Convention against Corruption.

The ruling coalition, rather than creating a sensible anticorruption policy, prefers to “buy” the votes it is missing in parliament in return for proposals of radical, constitutionally dubious anticorruption laws proposed by Paweł Kukiz’s circles.

Corruption scandals involving government figures remain unexplained. Instead of a reform of the civil service and the entire central administration, the government is siphoning off more and more competences and resources to dozens of agencies and special funds operating with little transparency and heavily restricted social control.

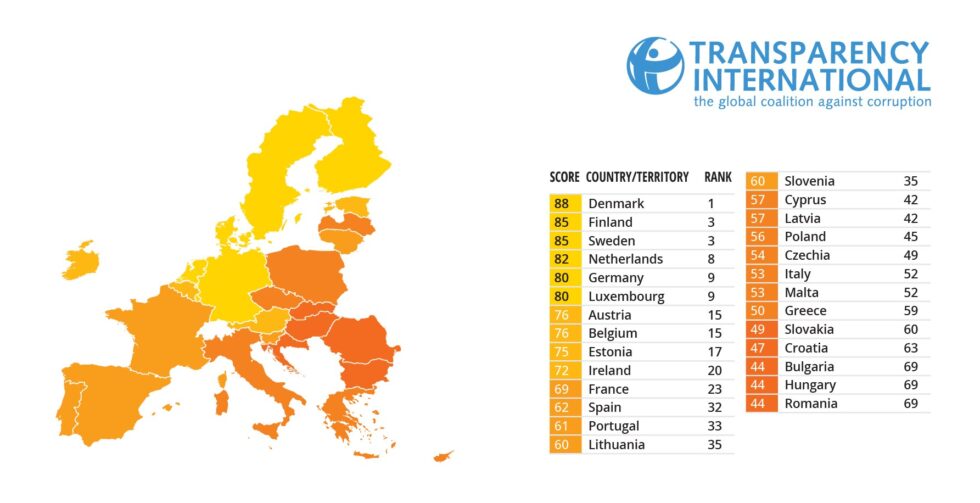

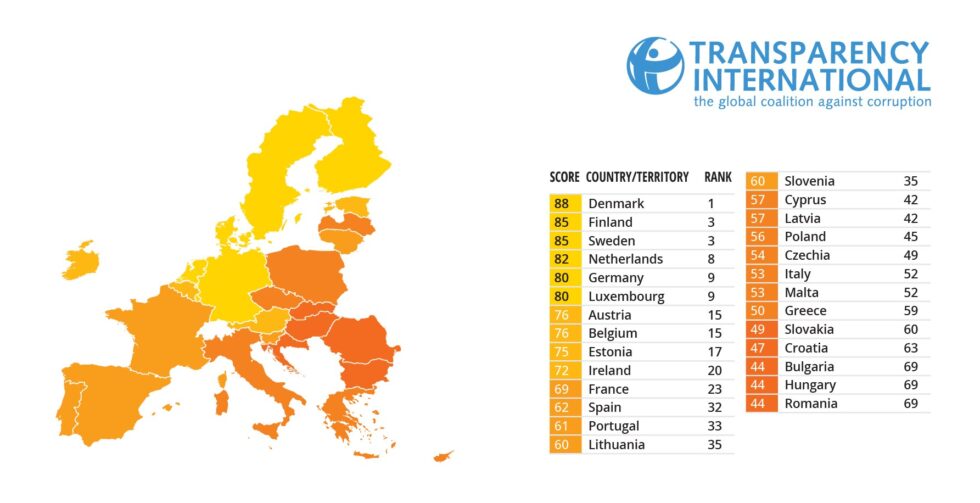

Transparency International’s Barometer unfortunately once again confirms that, far from chasing the leaders in the fight against corruption (Finland and Denmark), Poland is moving ever closer to the pariahs of corruption (Hungary, Romania, the Czech Republic or Bulgaria).

English translation by Ben Koschalka published in Notes from Poland.